The rise of populist radical right movements goes hand in hand with the politicization of history. Historical narratives are powerful tools that can shape public perception, reinforce ideologies, and legitimize political agendas. Focusing on the Alternative for Germany (AfD), we discuss with Matthias Dilling and Félix Krawatzek how the party’s strategic engagement with Germany’s collective memory intersects with broader trends in Europe and beyond.

From Milei’s nostalgic vision for Argentina to Romania’s recent electoral scandals that brought back echoes of the country’s fascist and communist past, history is a battleground for defining national identity and social values.

The interview sheds light on the role of the past in shaping the future, offering critical insights into the challenges posed by historical revisionism and the opportunities for fostering a more informed public discourse.

Enjoy the read…

1) Before we dive in, can you share what motivated your focus on the politicization of history? Were there particular authors, real-world events, or personal experiences that inspired this direction in your research?

Studying how politicians draw on history to defend a particular political argument has been somewhat of a niche question in political science. However, political discourse across many countries in Europe and beyond has shifted over the last decade and (re)interpretations of the past have often been central to this shift.

For example, think about Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again”, Jair Bolsonaro’s promise to return Brazil to the past, or Germany’s AfD campaigning on restoring a “normal” Germany. We observed this trend, and it resonated with our broader interest in historical continuity and political change.

One of us has contributed to research on historical institutionalism and the development and adaptability of political parties, and the other to research on memory politics, both theoretically and with a focus on European and Russian politics. For us, history matters because how past experiences are interpreted shape political rules and behavior. As a result, those who have the power to shape the meaning attributed to past events have decisive interpretive authority over politics.

Article here.

2) Why do you think that historical narratives are so important today, especially for the populist radical right? How does collective memory shape present-day politics and social dynamics?

In times characterized by accelerated change and uncertainty, it helps politicians to gain in popularity when they can offer a clear narrative of who we are as a society, where we have come from, and what binds us together. This is certainly not unique to the last two decades but has accompanied nation-building since (at least) the 19th century. More recently, we have seen such tactics emerge forcefully in authoritarian countries like Russia, where the Kremlin has used the past to justify foreign and domestic policies, but also in democracies that have grappled with how to relate to the shameful elements of their own past, like periods of authoritarian rule or colonialism.

Such historical narratives can have important long-term consequences. Germany is a good example. Since the 1950s, the country shaped a memory that emphasized Germany’s collective responsibility for Nazism, the Holocaust, and World War II. This narrative played an important role in solidifying the legal restrictions imposed by Germany’s post-war “militant democracy” and the discursive norms around what is acceptable to say in public. At the same time, the predominance of this narrative especially at the elite level contributed to the growing demand for different (revisionist) interpretations of history, which the populist radical right tabbed into.

Leveraging history is crucial for the populist radical right to promote their agenda. Their notion that a corrupt elite has robbed the virtuous people implies the existence of a better time in the past. Paul Taggart has captured this in the notion of the “heartland” – an ideal world that is “constructed from the past” and used to invoke a sense of nostalgia. In contrast to the self-critical examination of past events that, despite its shortcomings, has been a cornerstone of an ideal discourse about history in modern democracies, these parties celebrate a cleansed view of the past that externalizes historical guilt and instead appeals to people receptive to stories about heroes and national greatness. By claiming to be the only bearers of historical truth, they stand in sharp contrast to the traditional democratic discourse about history and instead “weaponize” the past as part of their goal to establish cultural control.

Article here.

3) Your work examines how the Alternative for Germany (AfD) discusses historical narratives in parliament. What key patterns did you find? Is AfD’s approach to history different from the approach of other parties?

In our analysis, the most surprising result is that in the period under investigation (2017-2021), the AfD representatives in the Bundestag talk about history like the representatives of other parties. They do not stand out in thus respect. However, things are quite different when we restrict the focus to the history of Nazism. As you know, some of the AfD’s historical interpretations have attracted wide attention like when Alexander Gauland downplayed the Nazi dictatorship as “just bird shit in more than 1,000 years of successful German history” or when the party invoked memories of the 1989 peaceful revolution that put an end to Communist rule in East Germany by campaigning for a “Wende 2.0”. Well, our findings confirm this impression: AfD representatives in the Bundestag use terms associated with the memory of Nazism much more often than parliamentarians from other parties.

Moreover, our sentiment analysis showed that when the AfD talks about history, it does so in particularly positive terms. While the AfD’s overall parliamentary language is significantly more negative than that of other parties, these differences are less pronounced and often disappear when talking about history. Around terms associated with the memory of Nazism, AfD parliamentarian’s language was significantly and substantively less negative compared to speakers from other parties. This supports the idea that the populist radical right contrasts a negative present with a glorified past.

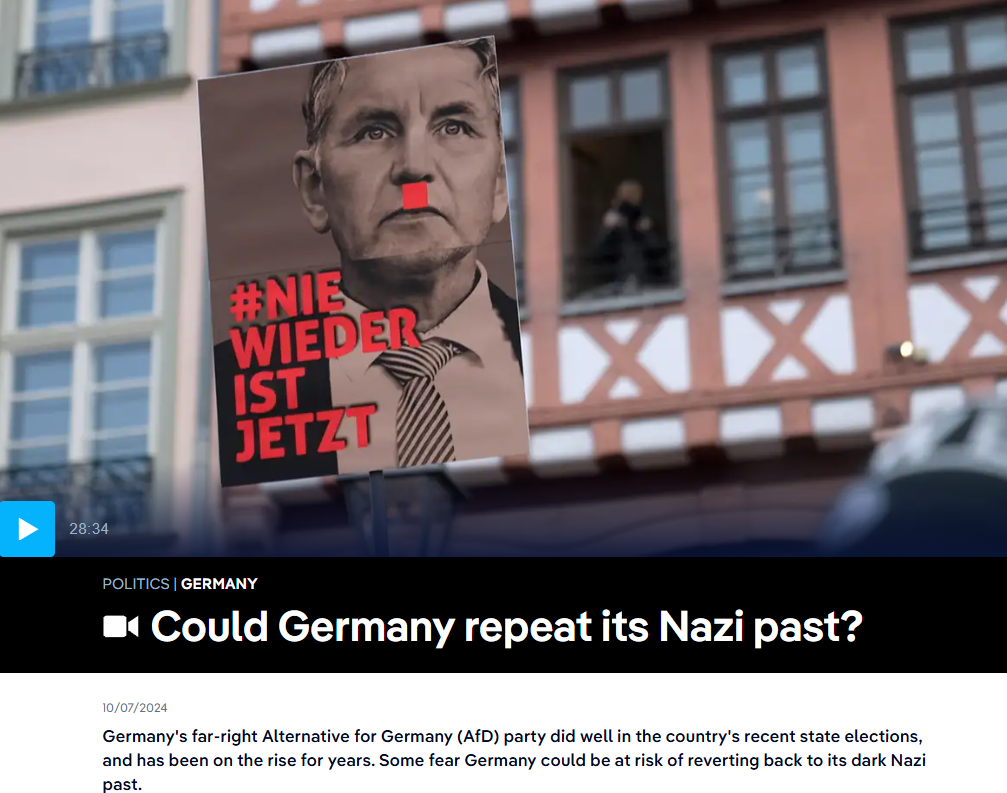

4) In line with your results, the AfD has been accused of being obsessed with the Nazi past, and its electoral success made some argue that Germany is at risk of reverting back to its dark Nazi past. From your empirical analysis, what insights did you gain about the party’s strategies and the implications of their historical framing?

The AfD’s most provocative statements about German history have made headlines and they are, beyond doubt, totally incompatible with the country’s democratic norms and demand to reverse the self-critical engagement with history that has been integral to Germany’s post-war integration into the international community. However, beyond those scandalous remarks, we want to point out that there is also a more subtle day-to-day engagement with history that can importantly reshape political discourse.

Our qualitative analysis, in particular, showed that the AfD engages in various historical themes beyond the Second World War and Nazism, including Communism, colonialism, Germany’s position in Europe, and the history of pre-1989 Germany. The AfD’s interpretation of these topics reveals that the party employs a situational and varied way of relating to the past, illustrating the ongoing strength of Germany’s memory regime and an awareness for AfD politicians of how to navigate it. They draw on various decontextualized historical themes to locate the AfD within the country’s historical imagination by accepting, minimizing, and rejecting the memory regime in place.

Article here.

5) As you mentioned, your article covers the period from 2017 to 2021—a time of significant growth and controversy for the AfD. In your opinion, how has the AfD’s narrative evolved since then, and what trends do you foresee for the future?

The AfD’s history is a history of radicalization. The party today is a far cry from its more moderate, primarily Eurosceptic beginnings, with at least parts of the party being classified as right-wing extremist (hence against democracy). Surprisingly, this radicalization has not hurt the party electorally. The AfD won 30+ percent in the three 2024 state elections in Eastern Germany and is currently polling just under 20 percent nationally. This suggests that the party’s initial “strategic frontstage moderation” is giving way to open defiance as it no longer seems to run the risk of being ostracized.

Statements previously considered taboo become increasingly acceptable, therefore we expect to see more historical revisionism in Germany in the future. Indeed, we know from comparative research that such a development can reduce the obstacles to even greater electoral success for the AfD and may undermine the democratic safeguards Germany had introduced after the war.

However, this development is not inevitable.

When the AfD’s lead candidate for the 2024 European election told an Italian newspaper that the Nazi’s main paramilitary force “were not all criminals” and it became public that AfD politicians had taken part in secret meetings to plan the mass deportation of asylum seekers and German citizens of foreign descent, the AfD encountered serious pushback.

This shows that while AfD narratives have grown in popularity, they are far from hegemonic. Future developments also depend on whether Germany’s other parties will, as some have done, give into the temptation of imitating the AfD’s rhetoric in an ill-guided attempt to win votes or whether they will stand up and defend the lessons Germany has drawn from its past.

6) What broader lessons can be drawn from the AfD’s engagement with German collective memory? How can your findings apply to other European countries where populist radical right parties, such as those in Hungary, Italy, or Spain, are also politicizing history?

The politicization of history is an intrinsic part of the populist radical right’s agenda, but its forms are shaped by the context. Germany provided a particularly complex environment for the populist radical right to navigate given the country’s rigid memory regime. In such an environment, we found the AfD to pursue substantive but multi-layered attempts at re-interpreting the past. This could be used as a blueprint by similar parties that operate in challenging environments, like VOX in Spain. Following the end of Franco’s regime, Spain chose to establish a “Pact of Forgetting”, leaving a scorched earth around the legacies of Francoism.

On the other hand, in countries with a less complex environment—like Italy, or with a greater emphasis on individuals’ freedom of speech—like the US, the populist radical right might pursue a blunter approach to historical revisionism.

7) Given the growing politicization of history, what role do you think scholars and educators should play in shaping public discourse around collective memory? How can research contribute to fostering a more informed and critical understanding of the past?

We think it is our responsibility as academics to unravel and inform about the causes and consequences of these developments. It does not mean imposing our own vision on how we should engage with the past: this is something every person needs to decide for themselves and advocate within society. However, it is our job as academics to identify and problematize socio-political trends, explain why and how they happen, and what they mean for political discourse and our political system at large.

We have witnessed an enormous increase in political polarization, which gives the impression of societies drifting apart and this, in turn, puts increasing pressure on democratic norms and procedures. The (ab)use of history and allusion to an alleged lost paradise or golden age have been an important part of this. We hope our research contributes to fostering an informed and critical engagement with these developments by identifying some of the strategies actors use to advance these narratives and destabilize long-established norms and processes.

Matthias Dilling is an Assistant Professor at Trinity College Dublin. His research focuses on political parties, the far right, and to what extent and how history continues to shape contemporary political outcomes. Before joining Trinity, he held positions at Swansea University and Oxford University, where he also did his PhD. His doctoral dissertation won APSA’s Walter Dean Burnham Award for the best dissertation in politics and history. He is the author of Parties under Pressure (2024, University of Chicago Press).

Félix Krawatzek is Senior Researcher at the Centre for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) in Berlin and PI on the ERC-funded research project “Moving Russia(ns): Intergenerational Transmission of Memories Abroad and at Home” (MoveMeRU). Previously he held a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellowship at the University of Oxford’s Department of Politics and International Relations and Nuffield College (University of Oxford), where he remained affiliated from 2018 to 2024. More information is available on his webpage.

One thought on “Interview #68 – Alternative for Germany and the “Weaponization” of History”