In this pantagruelic interview, POP discusses with Luke March about left-wing populist actors across Europe, the US and Latin America, the legacy of the Communist past, and the evolution of different families of left parties. We also talk about the Great Recession, the migrants crisis, Brexit, neo-liberalism, and the possible directions for the Left.

Luke March is Professor of Post-Soviet and Comparative Politics at Politics and International Relations, University of Edinburgh, and Deputy Director of the Princess Dashkova Russian Centre, also the University of Edinburgh. His main research interests include the politics of the European (radical) Left, Russian domestic and foreign politics, nationalism, populism, radicalism and extremism in Europe and the former Soviet Union. He has published in a range of journals including Party Politics, Comparative European Politics, Europe-Asia Studies and East European Politics. His books include The Communist Party in Post-Soviet Russia (Manchester University Press, 2002), Russia and Islam: State, Society and Radicalism (edited with Roland Dannreuther, Routledge, 2010), Radical Left Parties in Europe (Routledge, 2011) and Europe’s Radical Left. From Marginality to the Mainstream? (edited with Daniel Keith, Rowman and Littlefield 2016).

Luke March is Professor of Post-Soviet and Comparative Politics at Politics and International Relations, University of Edinburgh, and Deputy Director of the Princess Dashkova Russian Centre, also the University of Edinburgh. His main research interests include the politics of the European (radical) Left, Russian domestic and foreign politics, nationalism, populism, radicalism and extremism in Europe and the former Soviet Union. He has published in a range of journals including Party Politics, Comparative European Politics, Europe-Asia Studies and East European Politics. His books include The Communist Party in Post-Soviet Russia (Manchester University Press, 2002), Russia and Islam: State, Society and Radicalism (edited with Roland Dannreuther, Routledge, 2010), Radical Left Parties in Europe (Routledge, 2011) and Europe’s Radical Left. From Marginality to the Mainstream? (edited with Daniel Keith, Rowman and Littlefield 2016).

Enjoy the read.

Bunker in Tirana (Albania) – Summer 2016

POP: In recent years, more attention has finally been devoted not only to right-wing populist parties but also to the left. Parties such as Syriza and Podemos, movements such as Occupy Wall Street and politicians like Bernie Sanders, reminded us that (more or less radical) left-wing ideas still circulate in public debates all over the world. But to understand the present, let’s first make a step back in time. What has happened to the European radical left after the collapse of the USSR? Which trajectories have been followed?

Luke March: It’s important to note that the radical left never went away. It’s true that the collapse of the USSR was profoundly demoralizing for most of the radical left parties, especially the remaining communists, and it destroyed the remaining legitimacy of a fair few of them (particularly smaller and more doctrinaire parties). In an earlier work, Cas Mudde and I described this as a period of ‘decline and mutation’. The decline was certainly more visible, but there were many changes going on under the surface. But attention was very much elsewhere. This, after all, was the notorious period of the ‘End of History’, and radical left parties, where they were noticed at all, were generally seen as ‘dinosaurs’ – hidebound, obsolete holdovers of the past with no future to speak of.

But the collapse of the USSR in some sense liberated the radical left: it removed much of their political stigma (the sense they were a foreign body in the party system), and finally gave them leeway to develop new ‘unorthodox’ policies without any need to consult Moscow (a declining practice since at least the 1970s in any case). So the first thing that was evident in the 1990s was that many parties started pursuing more open, inclusive and non-ideological strategies, trying to incorporate different strands of the left (including formerly utterly adversarial ones such as communists and Trotskyists). They fostered broad, inclusive coalitions, either temporary or in more permanent institutional forms. The archetype of such a strategy was the Italian Rifondazione Comunista – a party which, for a time at least, bridged old-school communists, left-wing social democrats, autonomists, social movement activists and more. Overall, we can say that the most successful parties tried to focus on pragmatic issues, linking themselves with salient social campaigns, and moving away from the rigours of ‘correct’ ideological doctrine.

@evoespueblo Evo Morales con la bandiera di Rifondazione! Via @ferrero_paolo pic.twitter.com/blzS6o2KGa

— PRC Padova (@PRCPadova) 20 giugno 2017

That said, there are still clear divisions in today’s radical left, mainly ideological but not solely those. We can identify ‘conservative communists’, i.e. parties that are highly traditionally Marxist-Leninist (even Stalinoid, in terms of being nostalgic for the main dogmas of the USSR, if not overtly the Generalissimo himself). The main examples are the communist parties of Greece, Portugal and Russia, although the latter is a nationalist deviation in the same way Stalin was after WWII. There are a more eclectic band of what we might call ‘reform communists’, i.e. parties which are communist in name, often for electoral reasons, but who have jettisoned significant parts of the communist legacy. Rifondazione Comunista would be the main party here – but you could also identify AKEL (the Progressive Party of Working People of Cyprus), the Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova etc. These are parties that are still formally speaking quite doctrinaire, but their public policy is fairly flexible and non-ideological.

Most of the remaining parties fit into a broad camp of ‘democratic socialists’ – i.e. they still commit themselves to Socialism as a transformative aim (even if they’re usually unclear about how to get there), but also are anti-Leninist and committed to deepening democracy. They’re also committed to the so-called New Left agenda (i.e. environmentalism, feminism, LGBTQ rights), to a greater degree than the other types of party. There are some stark differences here – generally the Nordic parties have gone the furthest in the ‘New Left’ direction, whereas others have had a more traditional ‘materialist’ class-based emphasis (e.g. Syriza until recently). Others still, e.g. the Dutch SP (Socialist Party, although it symptomatically tends to go by its initials these days), are little different from left-wing social democrats (the SP has even described itself as ‘social democracy plus’).

There are, of course, many extra-parliamentary revolutionary left groups, many still quite clearly marked by Trotskyist or Maoist origins, others trying to adopt more inclusive strategies akin to their parliamentary brethren (e.g. the French New Anti-Capitalist Party). It’s a feature of the party family that most countries have several such micro-groups. They rarely have much electoral weight, but they are often staunchly critical of the main radical left parties, and compete with them for voters and activists.

Transnistria – Summer 2016: in Tiraspol the Soviet past is still very much present.

Of course, as your question rightly focuses, there are left-wing populist parties. Populist traits are present across the party family (after all, most have a strong anti-establishment ethos), but are most closely associated with the democratic socialist ideological core, which is less doctrinaire and more eclectic (after all, an authentically Marxist-Leninist party can’t be truly populist, since it relies on an elitist conception of party which is supposed to educate the masses). The decline of Marxism-Leninism has created more scope for the left to experiment with populist strategies. Before Syriza and Podemos, there were a few parties who had a pronounced populist streak, not least Die Linke in Germany and the Dutch SP. But it’s only since the Great Recession that these strategies have become more prominent and more successful.

POP: Do you think that the ideological convergence of the political system – or the Third Way à la Blair – opened the space for both right and left radical parties as well as populist ones?

Valparaiso (Chile) – Spring 2016

LM: It’s the perception of convergence rather than any measurable convergence in party programmes that is arguably more important, but to the degree to which this is politicized it is important, yes. Certainly, the radical left in particularly has gained great traction through the so-called ‘vacuum thesis’, the idea that the social-democratic left has abandoned its own core policies and heartlands to pursue alternative-less neo-liberal policies. There was a joke that the British radical left used to tell – ‘What’s the difference between Tony Blair and the Tory leader? None, they’re two cheeks of the same arse!’

Of course, at least in terms with how social-democratic governments have dealt with immigration, we can see the perception of ‘establishment’ parties pursuing identikit policies that prioritise globalization and neglect their traditional supporters as underpinning the rise of the radical right as well as left, as it became clear for us in the Brexit referendum. There is a core of truth to this, but it is exaggerated. Even under Blair, there were very distinct political differences between Labour and the Conservatives on the economy, Europe, immigration etc. However, the critical thing for the radical left was the essential similarity over post-Thatcherite political economy (i.e. a largely shared approach to market deregulation, privatization, public sector reform etc.). This goes under the name ‘neo-liberalism’, which has become a catch-all swear-word for denigrating the social-democratic left which is usually used entirely uncritically. For instance, for many on the British left, the Blair government is near-criminal because (apart from the undoubted fiasco of the Iraq War), it pursued ‘neo-liberal’ policies. If you want a more nuanced view of the Blair government, you should read the diaries of Chris Mullin, a left-wing former junior minister under Blair. For all his many criticisms of this government, he utterly rejects the idea that it achieved nothing for the left, especially in issues such as poverty reduction and investment in public services.

The evils of neoliberalism explained rationally and cogently by the great Noam Chomsky. https://t.co/LnQW3LVRdg

— Prof Tahir Abbas (@TahirAbbas_) 11 luglio 2017

POP: Put it differently: is there in Europe any left party that manages to be successful without becoming populist or moving to the center?

LM: Yes, there is still scope for an authentically radical left position which isn’t populist. The Nordic parties (in particular the Icelandic Left-Greens, who governed from 2009-2013) have never been particularly populist. As I mentioned, some of the conservative communists have remained more-or-less stable without becoming very populist, except in a very fleeting sense. And then one of the most successful parties of all (the Cypriot AKEL) has been a governing party largely because it is pragmatic in its alliance seeking, but also very traditionalist in its relations to its long-term supporters. It depends I guess on one’s definition of ‘successful’. Some parties are perfectly content with a niche position, and/or not changing their existing strategies very much. If they want to branch out beyond that niche position, then populism is obviously attractive. It’s also true that few of the non-populist parties are particularly dynamic, and some are evidently struggling.

POP: Is there a modern winning-formula when it comes to left parties, or the electoral performance is mainly linked to contextual national circumstances?

LM: It’s certainly more the latter than the former. The radical left has overcompensated to some degree, having gone from being agents of the third international to thoroughly ‘nationalised’ parties, who may maintain some internationalist aims but who are often rather suspicious of structured transnational co-operation and even, on occasion, of learning from each other. The radical left is, after all, one of the most chaotic and diverse party families at international level. Moreover, parties’ national circumstances are extremely diverse. Many countries have a small parliamentary radical left; in a handful the radical left is the dominant left party, but in many more (Britain included), there is a cacophony of struggling micro-parties.

The national circumstances are clearly better in some countries than others (after all, it’s no accident that the radical left is currently relatively strong in Greece, Spain and Portugal, countries which have been hardest hit by the Great Recession, and where the left still has an entrenched legitimacy through its role in resisting the dictatorships in the 1970s and before). That’s said, there are enough helpful national circumstances in most countries to have a stronger radical left than currently exists – e.g. poor economic conditions such as high unemployment, inequality and poverty, so ultimately parties are strongly influenced by national conditions, but they’re not the prisoners of them.

With that in mind, a winning formula can certainly be identified. There is no ‘magic elixir’, and it is certainly not the case that populism alone wins the day. Rather there are a number of ingredients, at least the plurality of which should be present.

- In terms of organisations, successful radical left parties are open but unified structures (i.e. they have pluralist internal currents but are not constantly riven by division or monolithically centralised as in the past); they also have telegenic leaders who are adept at playing the media game and expanding the party message beyond the core electorate (think Pablo Iglesias), but nor are they entirely dependent on them; their organisations are open to broader social and political movements, and able to connect with specific social struggles.

- In terms of messages, they are flexible, non-dogmatic, and manage to combine protest sentiment with ‘responsibility’ in terms of aptitude for government (e.g. how Syriza had both a protest face directed at the social movements but also claimed to be building the ‘government of the Left’); ideologically, they move beyond abstract socialism or even anti-austerity to focus on a number of concrete social issues, e.g. poverty, housing, debt.

All the above are fairly unspectacular, common-sense ingredients, but I bet we can all think of many an example of the radical left doing the precise opposite. In Britain, I immediately think of former Respect leader George Galloway appearing on the programme Celebrity Big Brother (see GIF below), ostensibly in the aim of reaching a broader audience. But he didn’t clear it with party colleagues, highlighting the lack of democracy in his organization. Any political content in the show was edited out, and the public was treated to him dressed in lycra pretending to be a cat, all the time while he was supposed to be a serving MP…

POP: The Great Recession and the constant flow of migrants from Northern Africa and Middle East intuitively constitute favorable conditions for the success of left parties, but empirically this does not seem to be the case. On the contrary, right-wing populist parties are on the rise. How do you explain this apparent paradox?

LM: I don’t see it as so strange. On the one hand, radical left parties, although they speak on behalf of the excluded, have long struggled to integrate non-traditional electorates, with fluid identities and places of abode, and this would be particularly the case in terms of new migrants who are not yet integrated into electorates (or even necessarily able to vote for parties that might ‘objectively’ defend their interests). On the other hand, more problematically, the Great Recession has clearly not been a left-wing moment, but a nationalist one. Contrary to the earliest expectations, when it seemed like there was scope for a new Keynesianism, it has been replaced by austerity politics, which are explicitly or implicitly parochial, selfish and quasi-nationalistic (focussed on the national debt as its ‘cri de coeur’ and on victimizing the state sector as ‘freeloaders’). That is hardly commensurate with an open doors policy towards migrants.

Clearly, national political, economic and media elites have found it easy enough to compartmentalize the response to the crisis nationally, rather than accept that there a broader response to capitalism needed. In such circumstances, with the rise of protectionist sentiments among their core constituents, radical left parties are in a bind, because most of them are in essence internationalist and pro-minority. They have generally stuck to their guns, even when an internationalist position is unpopular domestically. Conversely, the radical right has fewer principles – many parties have adopted a quasi-left protectionist economic position while remaining staunchly anti-immigrant. In other words, they can steal the left’s clothes, but not vice versa. Very few radical left parties have been able to escape this dilemma. Jeremy Corbyn has managed, at least to date, in as much as Labour has been able to hammer home a consistent message blaming economic reasons for the pressure on public services, rather than immigration per se, but even Labour has been unwilling to challenge the dominant consensus that immigration into the UK needs to be cut.

POP: About Corbyn. After rivers of ink flowing in an attempt to understand the debate around Brexit, it is still unclear the position taken by the Labor Party (and therefore by Jeremy Corbyn) on this matter. How do you read the left-right divide in the vote for the British withdrawal from the European Union?

Zurich Spring 2017 – No Border | No Nation

LM: You’re right. The Labour position has often been a shambles, with contradictory statements from leading officials within minutes of each other being the only common theme. However, Labour has managed, perhaps more by luck than design, to fall into an apparently more consistent position where accepts the referendum result but opposes the Conservatives’ Hard Brexit and will subject any deal to scrutiny, including tests of whether it minimizes disruption to jobs and the economy. In the June election, this allowed it to speak to Remainers who oppose Brexit or accept it with caveats, and to some Leavers who want a measured transition from the EU. Nevertheless, the position is full of contradictions, not least the aspiration for ‘access’ to the EU Single Market and Customs Union, while accepting that freedom of movement will probably end, which the EU has repeatedly said is ‘having your cake and eating it’. This makes sense as an opposition strategy designed to focus on the economic repercussions of the UK government’s reckless abandon, but is not a coherent government position, and arguably little better than that offered by the Tories. It is unlikely that this position would long survive a putative Labour government’s first negotiation tranche.

In terms of the Left-Right divide on the vote, it maps onto voting positions in a broad-brush way. Broadly the Right voted Leave (UKIP, DUP, and the majority of Conservatives) whereas the Left voted Remain (the SNP, Plaid Cymru, and ca. two-thirds of Labour). The problematic factor is the UK’s majoritarian electoral system, formed of local constituencies. The majority of constituencies voted Leave, as did over two-thirds of Labour constituencies, particularly in the Midlands and North. Whereas the majority of Labour voters in said constituencies still voted Remain, it has made Labour particularly neuralgic about openly opposing Brexit, and indeed for a long time prior to the last election it looked like there would be a ‘nuclear winter’ for Labour in the North, with its former safe seats falling like dominoes to a pincer movement from UKIP and the Conservatives. At the least, Labour’s current strategy mostly shored up its vote in Leave areas, while it was able to take many Remain areas from the Conservatives.

Beneath the Left-Right divide, there are other sub-divisions. On the Right, there is a division between economic Brexiteers (the vision of the UK as a major neo-liberal trading nation) and cultural Brexiters (‘getting our country back’ to a pre-EU and pre-mass immigration ideal). On the Left, the position is more homogeneous – although there was criticism of the EU, EU membership had strong support among the more urban and younger strata that tend to support the left, as well as among the key trade unions still affiliated to Labour. However, the ‘cultural Brexiteer’ constituency clearly had strong representation among core Labour areas, particularly in the Midlands and North, where the idea that stretched public and welfare services were at least partly the result of permissive immigration took hold.

Also highly relevant is a ‘Lexit’ constituency – the idea that leaving the EU’s ‘capitalist club’ can allow the emergence of a kind of ‘socialism in one country’ freed from the dictates of market Europe. Numerically, this group is very small – situated in some of the tiny ex-Trotskyist groups like the Socialist Party of England and Wales, Counterfire and the Socialist Workers’ who have some influence among left and social movement milieux. However, it has had disproportionate relevance, because Corbyn and key members of his team, especially John McDonnell (the shadow Chancellor) and Seumas Milne (his chief strategist) are convinced Leavers, even if they are publicly ambiguous. Their position is at odds with much of the party they lead. They favour free movement, but are against the single market, thus potentially clashing with both the main Remainers and Leaver positions. That their position is so different from the bulk of their party is one explanation for Labour’s fuzzy Brexit position.

Of course, this position was critical in the Brexit referendum itself. Corbyn’s ambiguous and unenthusiastic position regarding the EU was highlighted in a TV programme (‘The Last Leg’) in the run-up when he stated that he would give the EU seven or seven-and-a-half out of ten. The astute commentator Anthony Barnett noted that Corbyn’s very grudging position had ‘all the passion of passing a turd’. It was emphatically not the positive, transcendent tone needed to sell the pro-European position in the face of a mendaciously vituperative anti-EU campaign. Of course, Corbyn’s alleged lack of fight for the EU was utilized by Labour MPs to mount a precipitate ‘coup’ against him after the Brexit referendum, the fall-out of which hamstrung the party until the recent General election.

It would of course be erroneous to blame Corbyn alone for the Brexit vote (which after all, was conducted in an arrogant and high-handed fashion by Tory PM Cameron, largely as a way of assuaging his party’s restive right; nor was there any demonstrably overwhelming public demand for it). However, Labour’s campaign was flaccid and un-coordinated, and dominated for large periods by Labour Leavers such as Gisela Stuart and Kate Hoey. Given the size of the Labour electorate, turning a ca. 65% Labour yes vote into the 70% or so that would have tipped the balance is not inconceivable. Corbyn’s arch-supporters deny this of course, but we can contrast what happened when he did actively and personally campaign (the 2017 General election), with when he didn’t…. Whether he can continue to combine his essentially Lexit views with the strongly pro-Remain sentiments of many of his most ardent supporters, is going to be a high-wire act, especially if Labour comes to power.

Perfect, damn perfect. Bravo (again) @SKZCartoons … on #Brexit. pic.twitter.com/T6lKB37Urt

— Far Right Watch (@Far_Right_Watch) 21 luglio 2017

POP: Would you define Corbyn’s discourse as left populism or merely a return to a traditional socialist Labour Party?

LM: It’s a good but difficult question. It’s more the latter than the former I think. The difficulty is because Corbyn is himself quite difficult to pin down. Unlike his mentor Tony Benn (who was a prolific diarist and thinker, and who was also very concerned meticulously to cement his position in history) Corbyn was previously a full-time campaigner, not in any way a theorist or ideologue. This is also true of many of his team, even John McDonnell, who is his closest current comrade. This means that his forte was in hitching himself to, and amplifying, existing campaigns, rather than putting forward original ideas or precepts. In essence, he was a doer – a great networker and facilitator, rather than a great speaker or orator. On the negative side, as some of his critics alleged, it has meant that there hasn’t been much depth to his positions, and they have at times appeared a little sloganesque. On the positive side, he is to some degree a blank slate on which his supporters can ascribe their own hopes and dreams. So to some he is an arch anti-establishment populist, to others a genuine socialist, to others still the next Prime Minister-in waiting.

Left-wing symbols in the Mexican community of Chicago

Of course, there are elements of left populism there. There has been a deliberate attempt, especially since the beginning of this year, to learn from Podemos, Syriza, Sanders, and to emphasise Labour as a movement. The Corbyn-affiliated Momentum group does this explicitly via its ‘People Powered Politics’. Corbyn’s team have, rather clumsily at first, admitted that they have been reinventing him as a left-wing populist. So this can’t be denied, and is probably a key reason why he has appealed to younger supporters, particularly those burdened with student debt and just entering the precarious job market.

However, it’s just one string to Corbyn’s bow. He can’t be an all-round populist in part by dint of the position he is in. Labour is not a populist party by heritage, and its post-war history hardly marks it out as an anti-establishment force either, nor would the bulk of the party’s MPs support such a position. Consequently, although his team has attacked Blairite ‘triangulation’ (moderation in search of the centrist voter), they’ve actually moderated or dropped some of their key policies, e.g. over unilateral disarmament or overt defence of immigration. So much of Corbyn’s populism has been on the stump, while his TV appearances have been much more emollient, presenting Labour as a prudent, pragmatic and sensible government-in-waiting. The recent party manifesto continued in that vein with a plethora of costed policies, given the impression of a serious, but nevertheless inspiring document. There were a few populist flourishes to be sure, but the invocations against the ‘rigged system’ were hardly more numerous than those in Ed Miliband’s manifesto, and certainly didn’t amount to a coherent anti-establishment critique. To be honest, it’s easier to observe populism in some of Corbyn’s key cheerleaders, not least the journalist Paul Mason, who is an ardent defender of insurgency politics against the elite and Momentum as an instrument in movementising Labour. Again, we have the sense of Corbyn as a cipher, whom different figures translate differentially for different audiences.

It’s worth noticing that the majority of Corbyn’s positions are thoroughly in tune with those of the Bennite tradition and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy from whence he came: e.g., the emphasis on mass membership, the need to democratize Labour, by empowering the mass and recalling elected representatives so that it can become a mass movement behind Socialist ideals. This has also weakened Corbyn’s populism because, at least until the recent General election, many of his appeals and actions were focussed on enabling the party membership as the means of mass mobilization (not least out of necessity, because of his weak position among his parliamentary colleagues), and therefore, it was often (rightly) alleged that he spoke more to the Labour’s selectorate than the electorate, or country as a whole.

So, the bottom line is that it is a traditional socialist position, albeit one with populist overtones. Of course, one reason for the bitter in-fighting is that it is not a position traditional to the mainstream of the Labour Party, where the Left has usually been a minority. The party was founded as a (broadly) socialist party, but also as the parliamentary wing of the trade union movement. It’s had an uneasy relationship with extra-parliamentary mobilization outside those narrow confines ever since, and there are many defenders of so-called ‘clause one socialism’ (i.e. via parliamentary methods alone), who are critical of Corbyn’s vision. The recent election result, where Corbyn and Momentum did help raise youth turnout especially, has hushed such voices. For now.

Any cross party commission on Brexit shd involve Shadow Cabinet – MPs who join by May’s invitation = 1932 material https://t.co/lSZpr92iRV

— Paul Mason (@paulmasonnews) 14 luglio 2017

POP: Corbyn in the UK and Sanders in the US seemed to have addressed issues at the center of discourses articulated by social movements such as Occupy and the Indignados, but they both lost the elections. Do you see the glass as half full or half empty? In other words, do you believe they came close enough foreshadowing a left renaissance or, on the other hand, they failed under the most favorable conditions therefore left discourses are simply outdated as the defeats of Socialist parties across Europe seem to demonstrate all too clearly?

Chicago (US) – Spring 2016

LM: Before the recent UK General election, I would have clearly differentiated the two, saying it was half full for Sanders and half empty for Corbyn. Now Corbyn is in clearly an advantageous position, as if the UK government falls in the next six months or so, he will likely as not become Prime Minster. For Sanders, I think context is important, and the fact that a radical socialist can come so close to securing the nomination in a country as anti-socialist as the US is very significant. And now he has the status as ‘the one that got away’, in terms of being the candidate that could have beaten Trump. We will never know for sure, and there are reasons to doubt this view of events, but given Clinton’s fiasco, it could be argued that Sanders could hardly have done worse. He’s been somewhat sidelined by the drip-drip of revelations about Trump and Russia, but to the degree that the Democrats have been focussed on exploiting (and distorting) these revelations for all they’re worth in the hope that the Trump administration will self-destruct, to the exclusion of really reflecting on the reasons for their defeat, or putting forward a positive agenda for beating Trump in 4 years’ time, then Sanders will potentially retain a prominent role as the left-wing conscience of the Democratic Party, albeit that he is unlikely to be their future nominee.

As for Corbyn the situation looked dire prior to these elections and most people — myself included — thoroughly underestimated his potential. But this wasn’t based on media or personal bias (at least for myself, although those factors are relevant for some), but on hard electoral data, not least the dire results at the most recent local elections (May 2017), which predicted that Labour was heading for a heavy defeat. And in performing so much against expectations, Labour shattered several so-called electoral laws in British politics, i.e. that the campaign doesn’t change much, that divided parties can’t do well, that leaders with low personal ratings can’t perform, that mass membership still matters, and that parties with poor ratings on the economy will prove unpopular. Had Labour performed as to expectations in this election, and been defeated, perhaps cataclysmically, this would have vindicated the critics. I.e. as Theresa May’s performance showed graphically, the Conservative Party are no geniuses. They’ve been in power for 7 years, overseen divisive austerity policies and the decline in living standards for many, and run and lost a particularly pernicious and unnecessary referendum. So this was an eminently winnable election. In that context, the Labour result is ambiguous, because even though they drastically outperformed expectations, they still lost quite conclusively and are a long way short of forming a governmental majority.

Conversely, there is a lot of truth in the Corbynite critique of social democracy – that another more centrist candidate, who might have run on a more emphatically pro-EU, pro-business platform with a softened criticism of austerity (or ‘austerity-lite’ as Ed Miliband was sometimes criticised for), couldn’t have held on to the Labour Leave vote nor galvanised younger voters to vote in the numbers they did. Mainstream social democracy is in dire trouble, reinforced by Macron’s victory and Schulz’s sagging poll ratings, so there is something to the argument that a more radical, bold and unflinching principled defence of socialist policies marks a clear statement of difference from social democracy’s compromising and cavilling record, as well as, for the first time in aeons, marking out substantial philosophical and policy differences from the Conservative Party.

At the moment, this argument is only half-made. In the UK electoral system, vote share doesn’t mean very much, and although Corbyn supporters have been arguing that Labour’s vote share is the most impressive since Blair’s 1997 victory (and substantially more than he gained in his last election in 2005, having lost several million votes), this election result shows one of the poorest conversion of votes to seats since the 1950s, since the party stacked up votes in many areas where it was already rather strong (in a similar way to how Clinton trounced Trump in California which helped her win the popular vote, without having any bearing on the electoral college score once she had enough to win the state). Labour still needs 64 seats to win a majority, and 92 to equal the seat share Blair got in 2005 even at his nadir.

As things stand then, it’s a half-full scenario. Labour’s manifesto and campaign clearly enthused many people and Labour is utterly dominant among the under-35s. The party’s opposition, having looked moribund and bereft of ideas, is now invigorated, and it is now able to put concerted pressure on the Conservatives. The party has momentum, ahead in the polls and clearly in pole position to win any general election held imminently, although I would personally expect the government to last at least a year or two, which makes Labour’s prospects muddier.

At the moment, we don’t know whether this is just a temporary parenthesis or the beginning of the end of the age of austerity, as many ‘Corbynistas’ will have it. I recall Tony Benn’s analysis of Labour’s 1983 defeat as being ‘remarkable’ because it showed mass support for ’a political party with an openly socialist policy’. We all know what happened next, as 14 more years of Conservative policy gutted the social-democratic state and Labour’s remaining commitments to socialism. So, until Labour wins an election and manages to govern long-term as an ‘openly socialist party’ without undergoing a Syriza-like conversion to the politics of TINA, then it’s a very theoretical and tenuous ‘victory’.

Call your Representative and Senators to demand that they #JoinBernie and support the #MedicareForAll bill #HR676 https://t.co/bYpx5aFJuX pic.twitter.com/ax0psQeUQY

— Jeanette🌹Corbynista (@JeanetteJing) 18 luglio 2017

POP: How do you see the future or left-wing populism in Europe? Will it become more prominent or right-wing populism will remain at the forefront?

LM: I think it’s important to put left-wing populism in context. As I noted, I don’t think it’s a ‘magic elixir’ that will suddenly revive the ailing socialist patients across Europe – it’s just one of many factors that can help the left survive. It’s also got disadvantages too – chiefly that populism is an ideology of opposition, which can maximize protest support by focusing on the cleavage between the people and the 1% and downplaying other (particularly ideological-theoretical) differences. Plus, it often involves the left fishing in the same pool of disaffected protectionist so-called ‘left-behinds’ as the radical right, and potentially compromising more genuine socialist policies. It’s not really a recipe for a cross-class coalition except in a negative sense.

Certainly, if we look at the three ‘archetypal’ left-wing populist forces in Europe, Syriza, Podemos and now La France Insoumise, then they have been pioneers in terms of rebranding the left as a popular force, attuned to national(ist) sentiment, and with a powerful critique of the establishment, and (particularly in the latter cases) with new identities and organisational form. On the other hand, their ‘success’ is rather dubious, most obviously in Syriza’s case, but Podemos has fallen well short of the hype, and Mélenchon’s project has barely started. A bigger issue for the radical left, given the inbuilt hostility of the financial-media establishment, is proving it can govern in any way different from the so-called neo-liberal social democrats before it. The recent examples, in Greece, Cyprus, Iceland, haven’t been promising in that regard (at all). So I think populism’s best role is as one element in a multifaceted party position that appeals to different segments of the electorate. To some degree, both Labour and Syriza have adopted this position.

In the longer term, there is clearly scope for left populism to increase. After all, the non-populist radical left is generally rather stagnant. So it’s a strategy that offers more opportunities than risks. However, right-wing populism is likely to remain in the forefront – the right is generally better at exploiting emotions and fears, and can better supplement a (however hazy and contradictory) economic critique with cultural arguments, which engage better in the context of the immigration ‘crisis’. Added to that, the radical left is still one of the most ideological party families, so it has trouble with the flexibility/agility needed to adopt unorthodox stances. Put another way, the radical right can purloin the left’s economic policies (by making token statements about welfare protections etc.) but the left finds it difficult to do this back, finding it harder to campaign on issues of national identity or sovereignty, even with a populist critique. Plus the right doesn’t generally suffer from the phenomenon of so many competing micro-parties.

Je propose un rassemblement populaire le #23septembre contre le coup d’État social d’Emmanuel #Macron. #LE20H #TF1

➡️https://t.co/PZn8myyPqE pic.twitter.com/q1UBaCKg76— Jean-Luc Mélenchon (@JLMelenchon) 17 luglio 2017

POP: To conclude, can you identify different strands of left populism in Europe, or they all articulate similar discourses concerning the struggle between the poor and the rich? And how is it different the left populist discourse in Europe compared to Latin America?

LM: As various analysts have said, populism is chameleonic, an ‘empty signifier’ or a ‘thin-centred ideology’. So it doesn’t have much independent content separable from its national and ideological context. So to this degree there are as many populisms as there are left-wing populists, all with specific accents. The similarities are that they are focussed on socio-economics (they may criticize political elites, but their main ire is directed at financial-economic elites and the political figures who act as their agents), they are basically inclusive (i.e. the concept of the ‘people’ includes many sub-strata, not least sexual and ethnic minorities, as well as immigrants), and that they still have a latent internationalism, even if they are predominantly nationally-focussed.

The fundamental difference between left-populism in Latin America and Europe is also explicable by context. Latin American populism is dominated by the history of national-liberation struggles against colonialism, and latterly US imperialism, in the context of personalist regimes, and a weaker heritage of industrialization, class politics, and orthodox socialism. So this populism is arguably nationalist first, personalist second, populist third and socialist bringing up the rear somewhere. One only has to recall how Castro and Chavez created socialist parties and regimes some time after gaining power.

In Europe, Latin American populism is translated via the theories of Laclau and Mouffe, and concrete links with the Bolivarian regimes. So Podemos, and now La France Insoumise are distinct in trying to develop the theory of populism reflexively and learn from the Latin American experience. This is most noticeable in their downplaying of traditional radical left party labels and doctrines, the focus on being neither left nor right, the heightened accent on political critique relative to economic, the embrace of national identity, and the use of their leaders as popular figureheads with direct communication to the masses (including by novel use of social media).

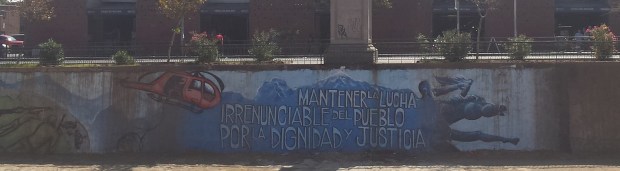

Santiago de Chile – Spring 2016 (“Let’s maintain the indispensable popular fight for dignity and justice”)

Other, earlier, European left-populists had some or all of these elements, but they were rather disparate threads that seldom amounted to a distinct package, nor crowded out more authentically socialist elements of the platform. Take the German Die Linke – its populism was arguably more developed when it was earlier the East German Party of Democratic Socialism articulating a defence of the East against West German elites. As Die Linke, it has seemed to have to ‘triangulate’ between its multiple different ideological and regional constituencies and its populism has become a bit more inchoate. For example, its party programme (2011) includes many populist elements (e.g. attacking ‘corporate bosses and the wealthy’) but is more noticeably for reinforcing its democratic socialist credentials in nearly every paragraph, e.g. the first couple of lines assert that ‘ as a socialist party [we stand] for alternatives, for a better future. We democratic socialists, the democratic left with different political biographies… ‘ etc.

Similarly, the left-wing populist parties in the UK that preceded Corbyn, namely Respect and the Scottish Socialist Party, had a highly developed populist strand but never fully transcended class politics. The same is probably true of Syriza, which, for all that it is often lumped with Podemos, is a coalition of several organisations, several of which are still strongly Marxist.

For all the focus on Podemos as a new type of party, many of its innovations are organisational not ideological, and it has had to adopt a more traditionalist left-wing profile over time, not least in its unsuccessful coalition with United Left in the last elections. Its strategic direction and the role of populism therein remain very fluid.

Overall, I think it’s very valid to focus on the strengths and weaknesses of left populism, but it’s important not to reify and decontextualise populism, whereby it becomes a rather meaningless catch-all label (somewhat like ‘Eurosceptic’ earlier – saying that the radical left is ‘Eurosceptic’ isn’t often particularly revealing either). For most, if not all of these parties, populism is just one element of a multifaceted identity.

I’m back at hotel now. #G20 protests are ALL OVER Hamburg! Democrats spend SO much money to fly paid protesters to Germany. Unbelievable! pic.twitter.com/fWfGNOWEwd

— Donald J. Trump (@RealDonaldTrFan) 6 luglio 2017

The featured picture on top has been taken by the author in Tiraspol (Moldova/Transnistria) in Summer 2016. It shows the parliament of Transnistria, with a 20 meters tall statue of Vladimir Lenin in front of it.

One thought on “Interview #17: Luke March on Left Populism”