In this interview with Maurits Meijers, we discuss the result of an expert survey that covers 250 political parties across 28 European countries. They do not simply ask if a party is populist, but how populist it is. Moreover, other dimensions of these parties are considered: their ideological position, their use of emotional tones, and much more. The data are available for downloading at Harvard Dataverse and you can play with the interactive tool to have a better grasp of the characteristics that come with populism.

Enjoy the read.

Populism and ideological positioning in Germany and the Netherlands. Notice, among other things, the top right corner, with Alternative for Germany, Party for Freedom, and Forum for Democracy.

POP) Tell us about the Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA). What kind of survey is it, which countries and which parties does it include?

Maurits Meijers) The Populism and Political Parties Expert Survey (POPPA) is an expert survey spanning 250 political parties in 28 European countries launched by Andrej Zaslove and me at Radboud University Nijmegen in the Netherlands. The expert survey set out to measure populism in political parties with a continuous measure.

The project started out in 2016 as I was working on a paper on the relationship between populism and political parties with Arndt Leininger (now forthcoming at Political Studies). We were looking for an authoritative list of political parties. Now we have the great resource Popu-List led by Matthijs Rooduijn, but that didn’t exist at time. We came up with a list of populist parties based on extensive literature reviews, not unlike the Popu-List.

Yet, in our literature review it was sometimes hard to adjudicate which parties are populist and which are not as scholars differ in the definitions they use and how they apply these definitions. So Andrej Zaslove and I had the idea putting that question to the experts.

POP) Some argue that, following Sartori, a party can be classified as populist or non-populist. You, on the other hand, prefer a continuous approach, telling us ‘how populist’ a party is. Why do you think this approach is better?

MM) Andrej and I felt that the usual, Sartorian dichotomous approach (i.e. which parties is populist and which party is not) is not complete. Some parties are more populist than others. Also political commentators in the media often use phrases such as “a very populist party”. This suggest that populism is a matter of degree. This is especially clear when looking at ‘border line’ cases. Is the Dutch Socialist Party populist, or the German Die Linke (Left Party)? Should we put it in the same category as the PVV and the AfD? The same goes for parties like the Italian Forza Italia (Go Italy) or the Flemish N-VA. Our expert survey data shows that these parties are indeed border line case. They show moderate levels of populism.

Populists are not big fans of complexity. The graph shows that the more a party is populist, the less it portrays political decision-making as a complex process, but rather as a common-sense solution to political problems.

POP) Why do you think that expert surveys are the best idea to measure European parties’ populism?

MM) First of all, I think it is important to stress that all methods for measuring party positions and ideology have their strengths and weaknesses. Expert surveys are a reputational method. That is, they measure the reputation of a party among informed experts. As such, it is an indirect measure.

But we believe this way of measuring populism is helpful for the concept of populism. First, the literature has long recognized that populism has multiple dimensions: people-centrism, anti-elitism, Manichean worldview, and the belief that the people are homogeneous, and that their interests are unitary. Populism is thus a multi-dimensional and latent construct. Therefore we believe we should measure populism in a multi-dimensional way that allows us to construct a latent variable of populism – and that is what the expert survey allowed us to do.

Another reason why we prefer to use an expert survey to populism over textual approaches is that populism can be very context dependent. The amazing research by Kirk Hawkins, Bruno Castanho Silva and Levente Littvay (and many others!) shows that the level of populism differs across different types of speeches and texts. There ism ore populism to be found in speeches than in manifestos, for instance. Hawkins and Littvay show that Trump is much more populist when he uses a teleprompter (i.e. reads a speech written by speech writers) than when he speaks freely. If we want to test hypotheses about the context dependency of populism these sources are extremely valuable. But if we want to get an overall picture of how populist a certain party is, the context dependency can be limiting, as we also argue in our Comparative Political Studies paper. Experts can take the entire information environment in to account, which can boosts its external validity – but perhaps at the cost of precision.

POP) The survey also measures other aspects of the parties, such as their ideological positions and characteristics pertaining to their organization and political style. So, what type of parties emerge as more populist? Is there a difference between left- and right-wing parties?

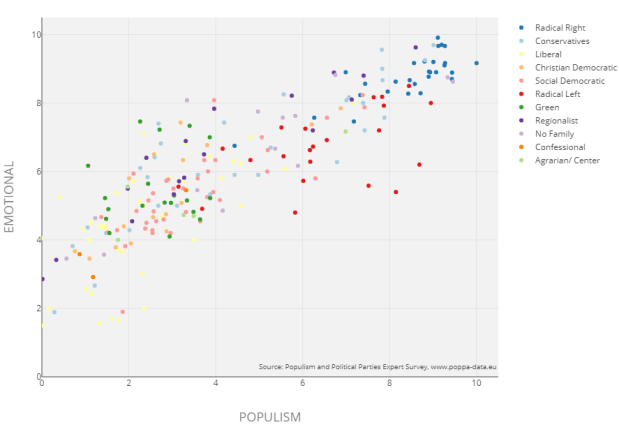

MM) The expert survey also included questions about political style, measured as parties’ propensity for emotional appeals and whether they portray politics as complex or not, and about party organization, measured as personalized leadership and intra-party democracy. We see a clear linear relationship between our latent populism variable and the items on political style. Yet, some highly populist left-wing parties are less likely to make emotional appeals and portray politics as common-sense.

Regarding the party organization variables, we also see a linear relationship between populism and personalized leadership and the degree to which the party commits itself to intra-party democracy, but this relationship is less strong. The German CDU and the Dutch GroenLinks (GreenLeft) are both marked by clear personalized leadership. This strongly echoes Cas Mudde’s arguments that these variables do not necessarily point to populism.

At the same time, we also see that if people rely on stylistic or party organization definitions of populism, they are likely to come up with a list of populist parties that is broadly similar – despite important differences.

Populist parties appeal to emotions such as fear, hope, anger, and happiness in their communication with voters.

POP) Unexpectedly, the survey seems to suggest that some centrist parties are very populist, such as M5S in Italy or the Cypriot Citizen’s Alliance (SYPOL). How would you explain this finding? Is it possible that those are populist parties that are very hard to place on a left-right continuum? Mattia Zulianello would include them in the category of “valence populism”.

MM) Andrej and I both believe it is crucial to separate populism from its attaching ideologies. As our data shows, some populist parties are strongly nativist, others are not. Some populist parties are strongly left-wing on redistribution issues, others are not. This is important as it allow us to explore and understand the variation among populist parties. For instance, some radical right populist parties support very conservative moral (family) values, while others don’t at all.

From that perspective it is not very surprising that some populist parties can be found in the centre of a ‘general’ left-right scale. The Five Star Movement in Italy has been ambiguous in its ideological profile – especially its more nativist turn in the migration crisis. Mattia Zulianello’s concept of ‘valence populists’ is intriguing. Yet, in practice I believe it is hard to distinguish valence populist from centrist populist as that would require an assessment on the credibility of a parties policy position.

Populism and ideological positioning.

Maurits J Meijers is an Assistant Professor for Comparative Politics at the Department of Political Science at Radboud University in Nijmegen. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the Hertie School of Governance, Berlin. His work has been published in outlets such as Comparative Political Studies, the Journal of Politics and the Journal of European Public Policy. His work focuses on questions pertaining to political representation at the national and European level.

Maurits J Meijers is an Assistant Professor for Comparative Politics at the Department of Political Science at Radboud University in Nijmegen. He holds a PhD in Political Science from the Hertie School of Governance, Berlin. His work has been published in outlets such as Comparative Political Studies, the Journal of Politics and the Journal of European Public Policy. His work focuses on questions pertaining to political representation at the national and European level.