POP finally interviewed Hans-Georg Betz, one of the major experts of populism. He has been professor of political science at various North American universities (Marquette University, Milwaukee; SAIS, Washington; York University, Toronto), and author of several books on radical right-wing populism and numerous articles and chapters on the radical right, populism, and nativism. Currently he teaches political science at the University of Zurich.

Since more than twenty years prof. Betz studies American and European populism in historical perspective. For this reason POP asked him to link the present situation of intolerance, racism, and new walls, with the roots of nativist and illiberal populism in the 19th century. This is particularly important because it allows to understand under which socio-economic situations populism and nativism become successful, which lessons we can learn from past populist outbursts, and what can be done to contrast them. Enjoy the read.

Columbus, Nebraska, 1890. People’s Party candidate nominating convention.

1) After Charlottesville the world realized that white supremacists, alt-right, and neo-Nazis are a reality in 21st century United States (in case Trump’s campaign wasn’t explicit enough). Which are the roots of nativism in the US? And how does Trump’s political discourse resonate with illiberalism, nativism, and anti-immigration movements typical of the 19th century?

American nativism has its roots in Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. Even before the American Revolution, there were strong strains of nativist sentiments, particularly against German settlers. As early as the mid-1750s, German migrants in Philadelphia were accused of possessing “oderous clothing” and “causing bad weather.” Their reluctance to learn English was interpreted as evidence that Germans were “innately stupid” and “ignorant people.” Benjamin Franklin warned that Pennsylvania was in danger of becoming “a Colony of Aliens, who will shortly be so numerous as to Germanize us instead of our Anglifying them, and will never adopt our Language or Customs, any more than they can acquire our Complexion.” For Philadelphia’s upper bourgeoisie, the Germans were clearly “racially” inferior compared to their Anglo-Saxon neighbors.

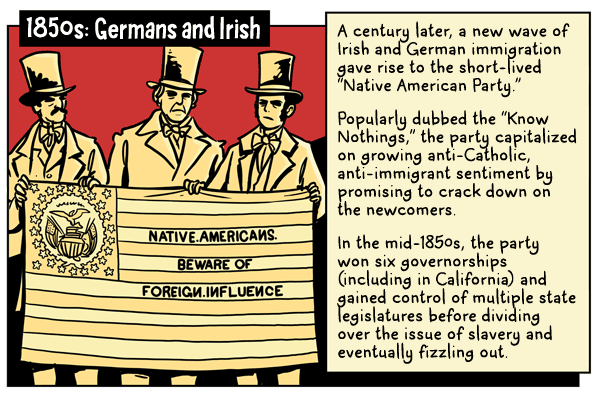

This picture is part of “Fear of Foreigners: A Cartoon History of Nativism in America”. By Andy Warner. Really worth reading it: https://ww2.kqed.org/lowdown/2016/09/12/fear-of-foreigners-a-cartoon-history-of-nativism-in-america/

Nativist passions erupted with great intensity and quickly turned political, however, in response to the first wave of mass immigration in the 1830s and 1840s. Here the main targets were Irish Catholics. Antebellum nativism reflected and expressed both traditional ethno-culturally inspired Anglo-Saxon contempt for the Irish and a violent repugnance for the “tyrannical popish faith” deemed to be fundamentally incompatible with American republican values. The nativists sought to defend and protect what they considered the country’s cherished Anglo-Saxon Protestant heritage and assure its continued supremacy. Nativist sentiments informed the formation of a number of secret associations, mainly in the northeastern states, culminating with the foundation of the American Party (popularly known as the “Know Nothings” in the early 1850s).

It is somewhat ironic, to put it mildly, that Donald Trump, the descendent of a German immigrant, would adopt the spirit and rhetoric of traditional Anglo-Saxon nativism and make it central to his political strategy. I would be more than surprised, however, if he happened to be aware of the irony.

2) Can we say that Trump’s victory, based among other things on the promise to build ‘the wall’ with Mexico to protect the border, marks the final triumph of the Know Nothings 150 later?

No. The Know Nothings of the 1850s never sought to put a complete halt to immigration to the United States. Their main (immigrant-related) demand was to extend the period after which an immigrant could become an American citizen to twenty-one years – equal to the time span it took for a “native-born American” to be accorded full citizen rights. The Know Nothings were less concerned with immigration per se than with immigrants being accorded the right to vote before they were fully assimilated into American society. The antebellum nativists believed that immigrants could – and should – be acculturated; today’s nativists are convinced that immigrants – particularly Hispanics – are not interested in acculturation. This is what is behind, for instance, “English-only” demands as well as various conspiracy theories centering upon the notion that immigration from Latin America, and particularly Mexico, is the first step in a strategy of Reconquista.

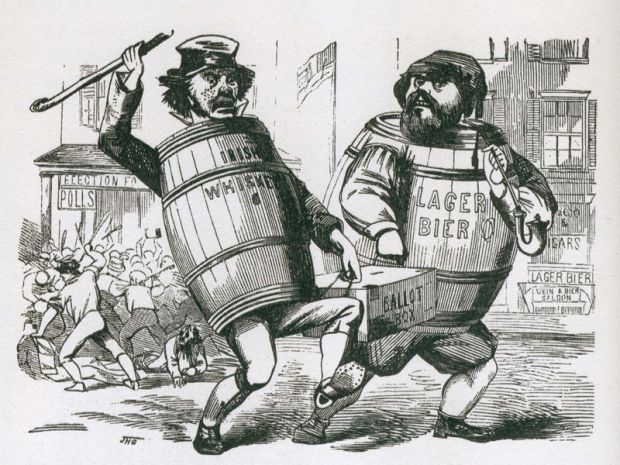

On the left the Irish whiskey drinker. On the right, the German beer drinker. In the middle, the ballot box.

3) A few decades after the Know Nothings, and a couple of hundred miles more West, nativism resurfaced in the US in the discourses of The People’s Party: in this case the target was mainly corporate capitalism and the collusion between Wall Street and the political establishment. Why, then, The People’s Party revived also nativist ideals, and which were the targeted groups?

The People’s Party, arguably the most important populist movement in American history, was a progressive movement (at least for its time), which to a large extent eschewed nativist temptations. This was particularly the case with regard to anti-Catholic sentiments, which, at the time, were again running rampant. In fact, a number of leading Populists, among them Mary Lease and Ignatius Donnelly, were Irish and Catholic. There were two exceptions, however. One was Anglophobia, largely directed against English absentee landowners and companies deemed harmful to the interests of farmers (in Colorado, for instance, companies that bought up water rights on which farmers depended for their survival) and particularly bankers, associated with the Gold Standard, which farmers held responsible for falling commodity prices following the “demonetization” of silver. The other exception was anti-Chinese sentiments, particularly in the north-western territories. The hostility against Chinese “coolies” was particularly strong among organized labor (i.e., the Knights of Labor), which was part of the larger populist coalition.

Chinese Coolies, 19th century picture.

It was not before the People’s Party disintegrated following the disastrous election of 1896 that nativist animosities can be found among some former populists. The main example was Tom Watson from Georgia – vice presidential candidate for the Populists in 1896 and once a vocal advocate for a populist alliance with African American farmers – who turned into a vicious promoter of anti-Catholicism and anti-Semitism as well as a leading driving force behind the disenfranchisement of African American voters.

4) Who was Georges Ernest Boulanger? And what kind of nativism was proposed by the members of the Boulangist movement?

Boulangisme was a populist movement, which for a few years shook the fin-de-siècle

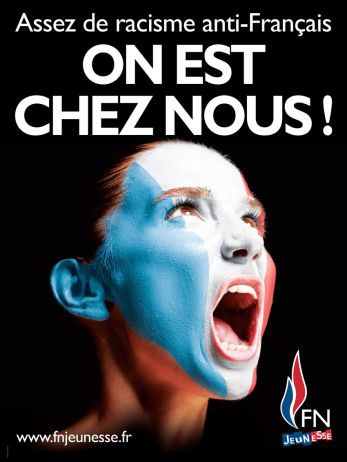

Front National (youth branch) poster: “Stop anti-French racism. We are at our place!”

French political establishment. It is named after Georges Ernest Boulanger, a popular general whose impeccable republican credentials earnt him the position of War Minister. His tenure proved short-lived, however. Relieved both of his ministerial and military position, Boulanger entered politics. His electoral successes quickly alarmed the political establishment, who accused him of plotting the overthrow of the Third Republic and forced him into exile. During his short political career, Boulanger gathered around him an ideological heterogeneous movement ranging from Blanquists on the far left to royalist monarchists on the far right, who financed his campaigns.

Boulangisme was vehemently anti-establishment (which they blamed for political immobilisme) anti-German (not surprisingly given the humiliating outcome of the Franco-Prussian War) and, to a certain extent, anti-Semitic (despite the fact that a leading Boulangist, Alfred Naquet, was Jewish).

5) When did Muslims start being perceived as a ‘problem’ and to be exploited as scapegoats by populist and nativist movements?

The first time I remember radical right-wing populist parties making reference to Islam and Muslim is in the late 1980s/early 1990s. I remember a flyer of the German Republikaner, for instance, which claimed that Islam was bent on establishing “religious world domination.” The Front national, in the early 1990s, warned that Islam was “in full expansion.” This was worrisome since history had shown that a “durable peaceful coexistence between the Christian nations of Europe and the Muslim oriental nations” was impossible. I also remember a cartoon on the back of a Vlaams Blok (now Vlaams Belang) pamphlet on immigration, which depicted a Muslim couple walking on the street looking up at a Flemish couple behind a window, saying “we should do something about these foreigners.” The Vlaams Blok was already anticipating Renaud Camus’ notion of the “great replacement.” These references to Islam and Muslims were, however, only peripheral to these parties’ anti-foreigner rhetoric. There was no mention of Islam representing an “ideology.” It was only with the war in ex-Yugoslavia and especially the Kosovo question that the discourse on Islam assumed a new intensity. A second factor was the growing public visibility of Islam and the growing demands on the part of Western Europe’s Muslim migrant communities, particularly with respect to building mosques and minarets.

6) Compared to the US the combination of nativism and populism is more consolidated in Europe. Since decades, parties such as Lega Nord, Front National, and the Dansk Folkeparti articulate populist and nativist discourses (with good electoral results). Why Europe has such a strong tradition of nativism and populism combined?

The United States has always considered itself as a country of immigrants, even if the question of what kind of immigrants the country wanted was always highly contentious. Against that, European countries have until recently claimed for themselves not to be countries of immigration. Migrants were generally seen as temporary “guest workers” who would eventually return to the country of origin. European societies considered themselves more or less homogeneous communities, an aspect which in turn was assumed to be the foundation of the sense of solidarity deemed indispensable for the maintenance of comprehensive welfare states. European radical right-wing populist parties in France, Austria, the Scandinavian countries and elsewhere play on each one of these themes. A prominent example is the Front National’s promotion of préférence/priorité nationale, which is central to the FN’s recent pronounced social turn under Marine Le Pen and particularly Florian Philippot.

Oui #Macron la submersion migratoire, le Peuple de France déteste cela.

La préférence nationale, cela vous parle ? #migrants #securite pic.twitter.com/k3Bqzmo6fh— COATIVY Muriel (@MurielCoativy) 25 agosto 2017

7) Maurice Barrès, who was elected in 1898 as a Boulangist at the Chamber of Deputies, proposed a populist project that was supposed to bring together nationalism and socialism. Should we list him as one of the intellectual ‘founding fathers’ of the (now dédiabolisé) Front National?

Maurice Barrès was one of those European intellectuals who are not easily categorized. On the one hand he defended the heritage of the Revolution and promoted himself as a left-wing socialist (in the French, not Marxist, tradition). On the other hand he became a prominent voice of anti-Semitism and the anti-Dreyfus right. His “national socialist” project was meant to reconcile the French working class with the republic in order to regain national cohesion as a basis for the revival of the French nation. With the expulsion of large parts of the traditional (Vichyite, anti-Semitic, or Catholic fundamentalist) extreme right (vehemently anti-Revolution and anti-de Gaulle) from the FN under Marine Le Pen, Barrès’ organic nationalism based on the notion of “rootedness” (enracinement) and identity (identité) could certainly be considered a point of reference for the new FN, even if there are relatively few direct references to him.

Maurice Barrès was one of those European intellectuals who are not easily categorized. On the one hand he defended the heritage of the Revolution and promoted himself as a left-wing socialist (in the French, not Marxist, tradition). On the other hand he became a prominent voice of anti-Semitism and the anti-Dreyfus right. His “national socialist” project was meant to reconcile the French working class with the republic in order to regain national cohesion as a basis for the revival of the French nation. With the expulsion of large parts of the traditional (Vichyite, anti-Semitic, or Catholic fundamentalist) extreme right (vehemently anti-Revolution and anti-de Gaulle) from the FN under Marine Le Pen, Barrès’ organic nationalism based on the notion of “rootedness” (enracinement) and identity (identité) could certainly be considered a point of reference for the new FN, even if there are relatively few direct references to him.

8) In Europe right-wing populism, because of its nativist component, is perceived as a “dangerous pathology threatening to undermine liberal democracy”. However also in Latin America, where populism is normally more inclusive, it looks like liberal democracy is threatened (the case of Venezuela being a textbook example). Isn’t it possible to conclude that populism, with or without nativist elements, is a threat to liberal democracy?

Populism is a kind of political discourse which seeks to replace representative democracy with a direct form of democracy which reflects the “genuine” will of “the people.” This assumes that there is a will of the people, i.e., that the people know exactly what they want, and that this will is unanimous. In its most extreme form, populism amounts to the tyranny of the majority, via a (often, but not necessarily) charismatic leader who promotes him/herself as the reflection of the people. This is why populist regimes, such as the one in contemporary Venezuela, tend to seek to undermine and ultimately destroy the mechanisms of liberal democracy with its checks and balances. Unlike the fascists and communists in the past, they rely on democratic institutional arrangements such as elections and popular referenda to bring about a fundamental transformation of the institutional system, via a process of “revolutionary constitutionalism,” which follows formally democratic procedures but is highly illiberal.

9) Is there any example of right-wing populist parties that are not nativist, and vice versa? And do you believe that contemporary right-wing populist movements are successful because of their nativist elements or rather because of their populist discourses?

Right-wing populist parties, by definition, are nativist parties. What defines the right is its rejection of the notion of equality. Right-wing populist parties such as the Front national reject the notion of equality. Otherwise the notion of national preference makes no sense. Nativism, on the other hand, is not necessarily associated with populism. Populism is always anti-elite. There is no good reason to suppose that an elite cannot harbour nativist sentiments.

Mario Borghezio (Lega Nord) in his kebab version

As far as contemporary radical right-wing populist parties are concerned, I believe that we tend to underestimate their populist appeal. Some prominent scholars in recent years have even suggested that parties such as the Front national should be labelled as “anti-immigrant parties.” This, however, ignores the extent to which they have mobilized and continue to mobilize anti-elite/anti-establishment ressentiments. In fact, a number of prominent contemporary radical right-wing populist parties, such as the FPÖ and the Lega Nord, only gradually adopted an anti-foreigner discourse, well after they had successfully mobilized widespread popular animosities against the “system” and its representatives (Proporz in Austria, Roma Ladrona in northern Italy). It should also not be forgotten that populism cum nativism is not always successful. The German Republikaner, for instance, were relatively successful mobilizing against the West German political establishment in the years prior to unification. Then they started to mobilize against various migrant groups, only to disappear from the political scene following unification.

10) In the 19th century it was industrialization and mass immigration. Now, at the origin of nativist resentment, there are mass immigration (again) and de-industrialization (the other coin of the industrialization process). Is it possible to conclude that socioeconomic turmoil is a powerful trigger for right-wing populism?

Socioeconomic turbulence and dislocation is one factor. The two great nineteenth-century populist mobilizations in the United States occurred at a time when the country faced profound economic depressions. These were, however, also periods of widespread political disaffection, profound disenchantment with the political class largely seen as corrupt and in collusion with economic and financial interests. The same could be said about the more recent waves of populist mobilization. It should not be forgotten that the first successful radical right-wing populist mobilizations occurred in some of the most affluent countries and regions in Europe; for instance the Scandinavian Progress parties, the Lega Nord, the FPÖ, and the Vlaams Blok.

Cover of Der Spiegel 47/2002. “Comrade Schröder. From the new center to Chancellor of the trade unions”

It is also true, however, that over time, most of these parties increasingly appealed to what in France is called the couches populaires, i.e. blue-collar manual workers, service sector workers, etc. This reflects, on the one hand, a response on their part to socioeconomic and socio-political change, from growing job insecurity to growing pressures on the welfare state; on the other hand, and perhaps more importantly, it reflects a response to the fact that what used to be called “the left” appeared to increasingly “give up” on them, pursuing instead identity politics (take, for instance, Holland making marriage pour tous a top priority at the beginning of his tenure while the country suffered from mass unemployment) and/or adopting the neoliberal creed (Gerhard Schröder was popularly known as Kanzler der Bosse). Worse, the left, both political and intellectual, have created the impression that they have nothing but contempt and distain for ordinary people, seen as parochial and xenophobic if not racist and too narrow-minded to understand the benefits of multiculturalism and globalization.

Anti-Trump protests in Chicago, 2017.

Recent events such as the outcome of the Brexit referendum and the election of Donald Trump are symptomatic of a widening sociocultural and socio-political polarization that can be seen in virtually all advanced liberal democracies, a widening gap between those “on top” and those “below”, between urban cosmopolitan elites and the provincial “heartland”. Central to this new cleavage is education, which correlates with opinions on immigration, globalization, and socio-cultural issues such as gay marriage and which also correlates with support of the populist right. This is also the factor which to a considerable extent has contributed to ever-widening inequality, both economic and in terms of life chances (e.g., health risks and longevity, marriage patterns via “assortative mating,” the passing on of privilege, particularly with regard to higher education, to the next generation). Again, this is nothing new. The Populist revolt of the 1880s/1890s occurred at a time of rapidly accelerating inequality, which came to be known as the “Gilded Age”. Donald Trump’s election has happened at a time which some of characterized as the second Gilded Age. The irony is, of course, that Trump is perfectly emblematic of the vulgar crassness of this age.

- POST-SCRIPTUM: Just one more thing regarding your question about the link between right-wing populism and nativism. I recently reread parts of Howard Palmer’s book on Canadian nativism, primarily in Alberta. At one point he discusses Social Credit, a populist (prairie populism) movement that emerged in the 1930s when nativism in Canada reached new hights, given the depression. Social Credit had rather authoritarian tendencies and appealed to some extent to anti-Semitism. Yet Social Credit never mobilized against immigrants. On the contrary, it actually had some of them (including Catholics and Mormons) leading positions and gradually was the party attracting a majority of the immigrant vote. Ironically, decades later, Preston Manning’s Reform Party had its roots in the Social Credit heritage. And the Reform Party certainly was nativist and anti-immigrants.

Logo of the Reform Party of Canada (1987-2000)

Logo of the Social Credit Party (1935-1993)

3 thoughts on “Interview #20 – 150 years of populism and nativism with Hans-Georg Betz”