In this thought-provoking interview, Jacopo Custodi challenges conventional ideas about nationalism by shedding light on its role within left-wing ideologies. Often associated with the right, nationalism is far from incompatible with progressive politics. Drawing from his latest book, Custodi discusses how left-wing nationalism manifests in diverse ways across European contexts, specifically in Southern Europe. We discuss the distinctions between left- and right-wing nationalism, the nuanced ways leftist parties engage with national identity, and the interplay between nationalism and populism. Reclaiming a sense of nationhood can serve progressive goals—though it requires careful balancing to avoid the pitfalls of exclusionary nationalism.

Enjoy the read…

When we think about nationalism we imagine parades and flags, images that evoke the radical right. The forces of the left, on the other hand, should be internationalists by vocation. Instead, your work convincingly shows that left-wing nationalism is alive and kicking. What are the main differences between right-wing and left-wing nationalism?

The issue here is that the word “nationalism” itself is controversial. Suppose we define nationalism by the aggressive, ethnic, and conservative connotations it often carries in public debate. In that case, nationalism does not belong to the Left in Europe. However, if we define nationalism as the politicization of national belonging, then the picture becomes more complicated and more interesting.

Indeed, left-wing independence movements, like those in the Basque Country, Catalonia, and Scotland, can be quite nationalist. Moreover, different degrees of nationalism can also be found within the state-wide radical Left. While some state-wide radical left actors reject any form of national identification, others do incorporate national-popular elements into their discourse, and still others even display a bold patriotic rhetoric, in opposition to a Right accused of betraying the country’s interests.

What is more, this isn’t just about degrees (from no nationalism to a lot of nationalism, so to speak); it’s also about the content. How do left-wing actors understand national belonging? As Benedict Anderson taught us, nations are modular, meaning they can be “transplanted, with varying degrees of self-consciousness, to a great variety of social terrains, to merge and be merged with a correspondingly wide variety of political and ideological constellations”. This suggests that national identity and belonging can take on different meanings and be tied to different sets of political values. This complex dynamic is what I try to explore in my book Radical Left Parties and National Identity in Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

Your book indeed focuses on three Southern European countries: Italy, Spain, and Portugal. What are the similarities in the use of left-wing nationalism in these countries and what are, on the other hand, the main differences?

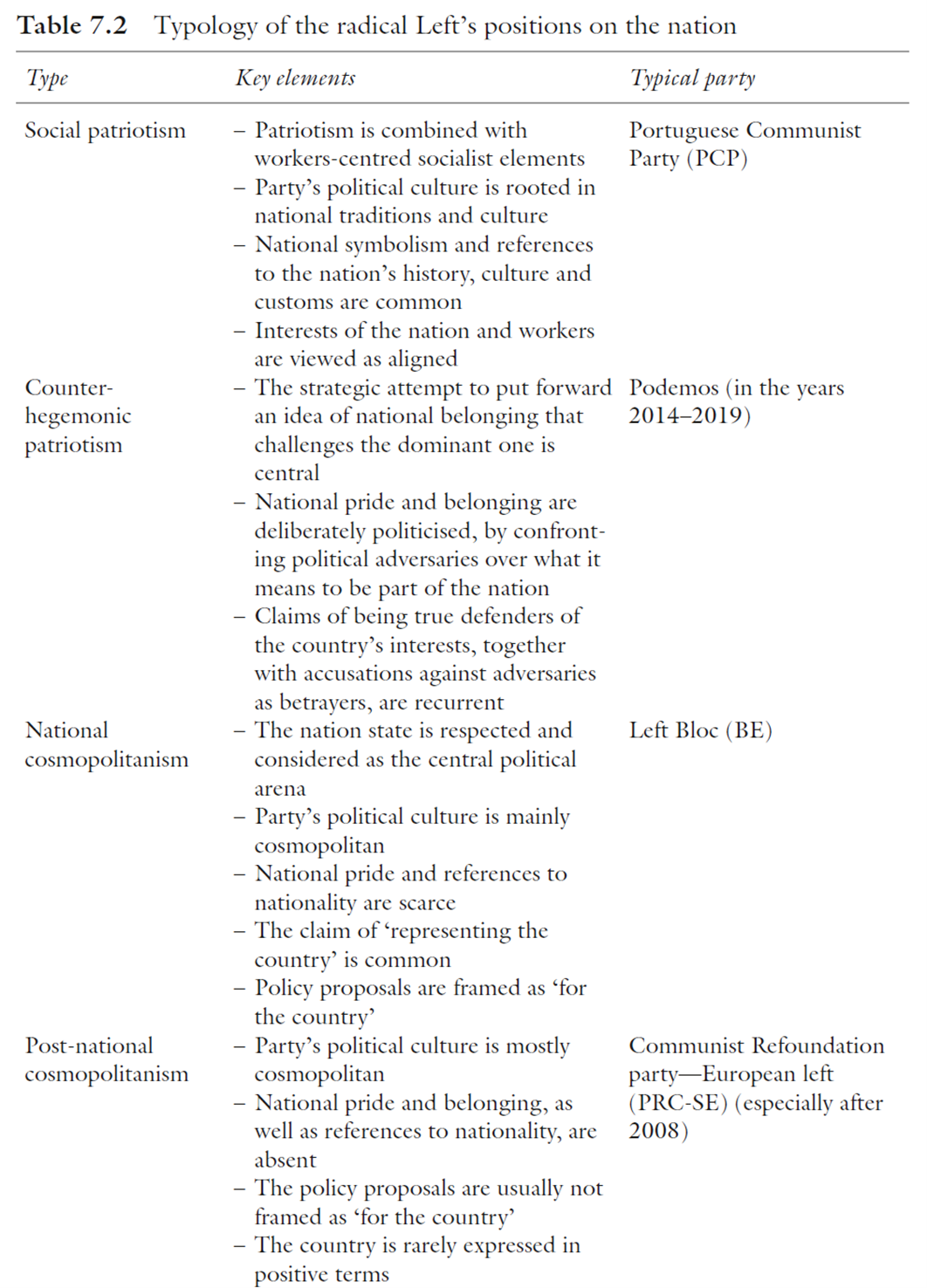

There are significant differences in how the radical Left deals with nationality in Italy, Spain, and Portugal. These differences largely reflect historical and contextual factors, but sometimes also arise from specific strategic choices tied to political agency, which can occasionally challenge structural constraints. This observation was, in fact, the starting point of my research: recognizing that ideologically similar parties can diverge significantly in how they approach national belonging. While I can’t go into detail here, I’d like to share a table from the book that summarizes the main ways in which the radical Left engages with the nation in these three countries.

Since your book was published, is there anything you feel aged like milk? On the other hand, what are the elements that you think will age like wine?

The book was published in 2024, but I use data from earlier years. Since we’re dealing with political actors that are constantly evolving, some things have already changed. The most notable change has been in Podemos’ political and ideological profile. I acknowledge this in the book, but my analysis of Podemos’ relationship with the nation focuses on its early phase. Therefore, a fresh analysis of how Podemos speaks about the country today would be important.

That said, beyond the normal evolution of politics, what I believe remains relevant in the book is the idea that, when studying how left-wing parties engage with national identity and belonging, we cannot simply ask whether they are nationalist or not – this is misleading. We need to understand how they perceive the nation, what meaning they give to it, and how they use that identity politically. It may seem like a simple point, but it’s something missing in previous studies on the European radical Left. Without wanting to sound arrogant, I believe this is the book’s key contribution.

Don’t you think that nationalism, because of the history it carries and the connotation it acquired over time, is a symbol that the left should keep away from? Is there really a non-problematic way to invoke nationalist ideas and values from a left-wing perspective without conjuring up monsters from the past? Going back to the subtitle of your book: rejecting or reclaiming the nation?

If pressed for a straightforward answer, I would say “reclaiming the nation”. However, it is crucial to discuss how to reclaim it, for what purpose, and to what extent. I am convinced that embracing national belonging and pride strategically, while redefining them with inclusive and progressive values, can help build consensus and challenge the Right’s dominance. That said, this approach is neither simple nor without risks, which must be carefully considered. For instance, if claiming the nation from the left results in reproducing forms of discrimination against migrants or minorities, then we are not pursuing it correctly. This is a normative and strategic issue I explore in depth in my other book Un’idea di Paese and, for English-speaking audiences, in a recent article for Jacobin Magazine.

Radical Left Parties and National Identity in Spain, Italy and Portugal. Rejecting or Reclaiming the Nation. Click on the image to follow the link to the book.

And now, the million-dollar question: what is the connection between populism and nationalism, and why are they so often confused? Is it possible to have one without the other?

This is a difficult question, one that I have tried to answer in a recent essay co-written with Michaelangelo Anastasiou. On the one hand, I believe it’s important to reject the association between populism and ethnocultural right-wing nationalism as if they were the same thing. They are not. On the other hand, the concepts of “people” and “nation”, to which both populism and nationalism refer, do share some common ground. In fact, the nation often produces rituals, symbols, and cultural references that play a key role in shaping popular identities and creating a sense of belonging among the people.

Even Antonio Gramsci, in his Prison Notebooks, sometimes uses the two terms interchangeably. I think the Tunisian intellectual Sadri Khiari explains this well when he says that “the semantic universe in which the concept of ‘people’ unfolds, and in which it takes on specific meanings, is generally constructed through the interplay, never identical, of three other concepts: nation, citizenship/sovereignty, and the so-called subaltern classes. What we can deduce from the variety of ways these concepts are linked is their flexibility, their permeability to one another, and their capacity to evolve and even blur together”.

In conclusion, I would like to discuss a paradox. The radical right has established solid international and transnational links, with frequent events across the world where they show a united front. For example, in October 2024, the leaders of the parties composing the Patriots for Europe in the European Parliament (a group that includes Orbán’s Fidesz, but also VOX, Chega, and PVV among others) attended the annual gathering of Salvini’s League. The impression is that the left is struggling to form a united front that goes beyond fights between opposing factions. Why do you think this is the case?

This sounds paradoxical, but it’s true: contemporary nationalist right-wing actors are often much better at forging strong international alliances than the internationalist Left. I don’t have any easy solutions to offer for this problem, and frankly, I don’t think easy solutions exist. The radical Left’s current inability to strengthen transnational cooperation is part of the broader crisis of the Left and is tied to the ideological and strategic fragmentation we also see at the national level.

If there’s anything we can learn from the Right’s international cooperation, it’s that national identity is not necessarily an obstacle to collaboration on a transnational scale. Hence, a leftist approach that rejects any connection to its own national history and national-popular symbols not only risks distancing itself from the popular classes but also provides no guarantee of stronger international cooperation. In the end, it’s all there in the 1848 Communist Manifesto: “Workers of the world, unite!”, of course, but for the proletariat to succeed, it “must constitute itself the nation”. These two elements are not only compatible but essential to one another.

Jacopo Custodi is a research fellow in political science at the Scuola Normale Superiore in Italy and an instructor at Stanford University and Georgetown University. His most recent books are Un’idea di Paese. La nazione nel pensiero di sinistra (Castelvecchi, 2023) and Radical Left Parties and National Identity in Spain, Italy, and Portugal: Rejecting or Reclaiming the Nation (Palgrave, 2024).

Twitter/X: https://x.com/JacopoCustodi