In this interview, Álvaro Sánchez-García explains the complex interplay between depopulation, political polarization, and voting behaviour in rural Spain. Drawing from his research, Álvaro challenges common assumptions about the political inclinations of depopulated areas, suggesting that rural grievances in Spain extend beyond economic anxiety. Rather, depopulation itself—paired with a sense of community loss—fuels a unique discontent that influences support for various political factions, not just the radical right.

The interview offers a detailed analysis of how shifts in demographics, amenities, and population density shape political preferences. While mainstream conservative parties have historically benefited from depopulation, when this decline intensifies, parties like VOX gain traction, positioning themselves as advocates for rural interests. This conversation provides an in-depth look at the rural-urban cleavage’s resurgence in Spain, underscoring the ways global shifts and depopulation drive new forms of political expression and local identity.

Enjoy the read…

For years now, we have been hearing about left-behind areas as great reservoirs of votes for the radical right. The idea that the Rust Belt votes for Donald Trump was widespread in 2016 and we still hear the same arguments repeated today. We also read analyses comparing the votes for the AfD in Thuringia, a place the 21st-century economy seems to have left behind, and how Trump might become president (again) by winning West Virginia, a symbol of the decline of much of rural and small-town America. Is there any evidence in the literature about this? Is it economic anxiety in de-industrialized areas driving the vote for the radical right?

Yes, without a doubt. There are two main explanations linking this economic decline and the vote for the radical right. On the one hand, resentment against the political elites whom they blame for the deterioration of their municipalities is a narrative that fits very well with populist attitudes in general and specifically with those of the right. Radical right-wing populist parties pick up on this discontent very well with their chauvinist and anti-globalisation messages, a process they blame for this de-industrialisation. On the other hand, another certainly interesting argument is that of nostalgia. I am thinking, for example, of Peter Luca Versteegen‘s remarkable article, in which the comparison evoked by nostalgia (between a theoretically good past and a bad present) leads to disaffection with governments and increases the likelihood of supporting radical right-wing parties. [See our interview with him here.]

Your argument follows a similar but, at the same time, crucially different logic. You claim that it is not necessarily economic anxiety, the loss of manufacturing-related jobs, or the grievances of the ‘losers of globalization’, but rather depopulation that affects voting behaviour in Spain, and that this does not only affect the vote for the radical right but all parties. What is the logic behind this argument? In what ways are depopulation the rural-urban cleavage connected, and how do they differ?

First, this work has been elaborated with the invaluable collaboration of my brilliant co-authors Toni Rodon (Associate Professor at the Pompeu Fabra University) and Maria Delgado-García (Research Assistant at the Pompeu Fabra University). We understand, in line with what other authors have written, that depopulation is the most cruel sign of decline (in a broad sense). It is difficult to witness an industry leave your municipality and realize that “because of globalisation” you have to look for another job. To see how your village, where you grew up and lived for so many years, is gradually disappearing is a harsh manifestation of the oblivion that rural areas in particular face. As a rural dweller myself, it is very hard to see your village gradually fading away. And this discontent fuels the radical right.

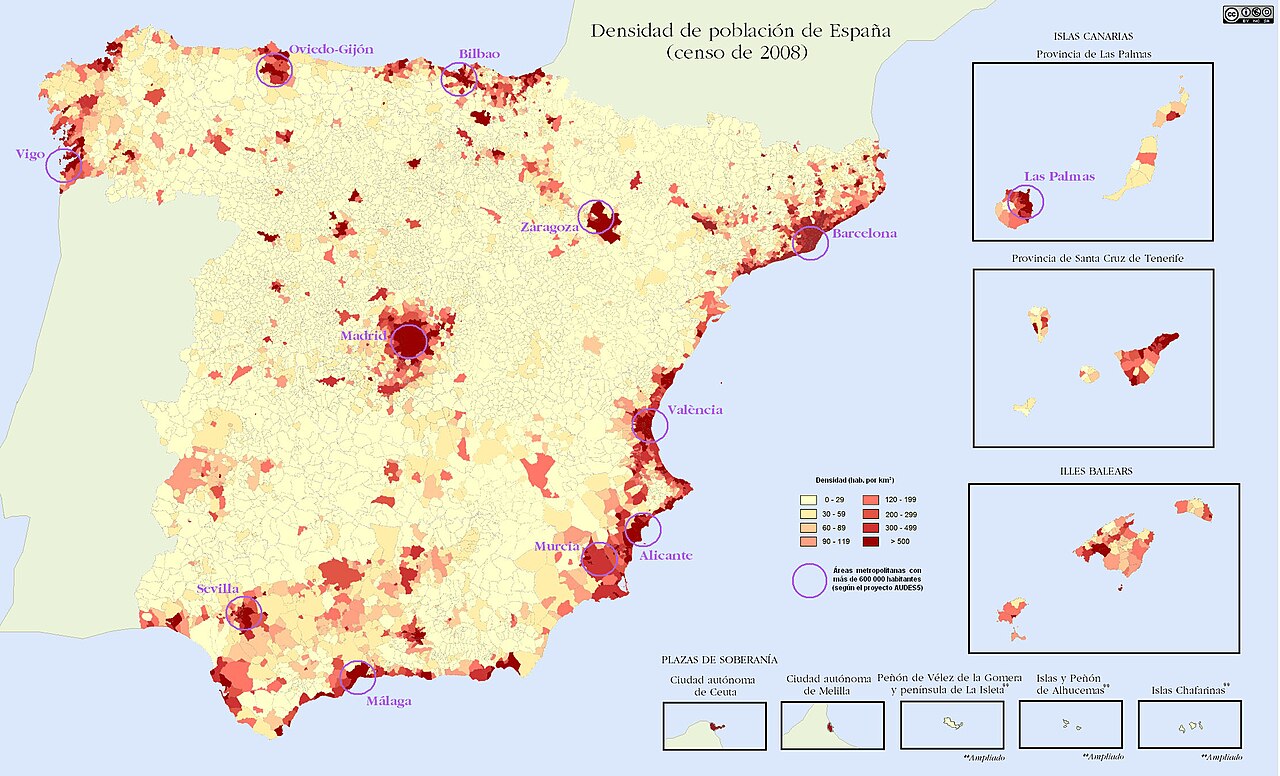

We believe that in Spain there is an intimate relationship between the rural-urban divide and depopulation. In general, demographers have shown that depopulation in this country is markedly rural. However, not all depopulating municipalities are rural, and not all villages are depopulating. Actually, many towns have grown a lot in recent years as a result of the tiredness of many people of the pace of life in the cities. I can think of cases close to me like Arroyo de la Encomienda in Valladolid or Carbajosa de la Sagrada in Salamanca, which is what Jorge López Dioni talks about in his interesting book “La España de las Piscinas”. However, this relationship varies depending on the context and dynamics of each country.

You study Spain and, in particular, Spain’s rural and sparsely populated interior provinces usually called ‘Empty Spain’, to the point that even a political party with that name has emerged, inspired by a similar experiment (Teruel Existe). What problems and grievances do these areas have in common?

These two provinces, in particular, are the two with the smallest populations in Spain. Their demands are mainly aimed at the creation of infrastructures such as roads and high-speed trains, and attracting business projects or public institutions (universities, research centres, and so on). All these proposals have the clear goal of retaining the population, on the one hand, and attracting new inhabitants as a result of the new jobs that would be created by these public policies, on the other. These non-state parties do not have an identity or cultural basis, but a purely materialistic one to guarantee the survival of the municipalities in their province.

You look at the effects of depopulation on voting behaviour. What are your findings?

We can summarise our results as follows: depopulation has benefited the mainstream right (PP, conservatives) and damaged the mainstream left (PSOE, socialist). We believe that this effect is not so much due to a change in political preferences as to a change in the composition of municipalities. Depopulation involves the emigration of highly qualified young people, a progressive profile, while the breeding ground left in these depopulating places is an ageing population with little education, which fits the profile of a conservative voter. Nevertheless, in recent years, when the situation of the municipalities becomes serious, support for VOX has increased to the detriment of the PP.

Moreover, you connect depopulation to other key characteristics of these communities: the municipality size, the change in the demographic composition, the variation in public services, and changes in the presence of amenities. How do these elements interact with depopulation in terms of voting behaviour?

Overall, these variables have not provided us with the expected information. With the data we had on public services and amenities (which were not many due to the lack of collaboration from public administrations), the results do not show that depopulation – together with the loss of these services – has any effect on electoral behaviour. Nevertheless, the size of the municipality and the presence of elderly people have yielded interesting results. The effect of population loss on the PP vote is greater in smaller municipalities and in areas with a greater presence of elderly people.

Talking for a moment about the populist radical right party VOX, what does your analysis reveal? Under which conditions depopulation produces an increase in the electoral success of VOX?

VOX is a peculiar party. It is a party that has performed better in urban areas while having a markedly ‘rural’ narrative. In this sense, our results show that in conditions of extreme depopulation (population loss, low population density, and negative vegetative growth) the support for VOX increases. This tells us that in municipalities where there is depopulation, the PP obtains better results, but when it becomes an issue of real concern VOX improves its performance, not the PP.

Is it possible that people living in rural areas and those living in cities are growing increasingly apart in terms of ideas, values, attitudes, and – ultimately – voting behaviour? If this is the case, what are the origins of this diverging trajectory, and what are be the implications in the long term?

Yes, without a doubt. Actually, much of the recent literature points in this direction. Jonathan Rodden’s book Why cities lose? The Deep Roots of the Urban-Rural Political Divide as well as Rahsaan Maxwell’s article come to mind. Economically, cities have experienced sustained growth and increased exposure to globalisation, fostering more cosmopolitan attitudes and greater openness to diversity. In contrast, many rural areas have been affected by de-industrialisation, the decline of traditional sectors and the migration of young people to urban environments, generating a sense of abandonment and resentment towards urban elites, perceived as beneficiaries of globalisation (which has also given rise to what is known as “rural resentment”). Also, migration dynamics to the cities leave rural areas with an older population, fewer people and traditional values. In contrast, the cities, which are younger and multicultural, adopt progressive attitudes. This demographic difference feeds the polarisation in values and voting behaviour.

In the long term, I think this is going to lead to more and more spatial polarisation between rural and urban dwellers. But as Toni Rodon says, polarisation also has a positive face. We will almost certainly witness the emergence of niche parties, especially in rural areas, as is already the case with the BoerBurgerBeweging in the Netherlands.

In their 1967 book Party Systems and Voter Alignments, Lispet and Rokkan identified four cleavages structuring our societies, with the centre-periphery (or rural-urban) cleavage being one of them. Until a decade or so ago, this cleavage seemed to have lost much of its salience. Do you think that we are now seeing its revival? If this is the case, why do you think this cleavage remains so crucial in so many contemporary democracies?

Yes, absolutely. I suspect that spatial polarisation (what we can understand as “place-based resentment”) is one of the reasons behind this resurgence of the rural-urban divide. The two explanations for the increase in this polarisation may be the difference in values mentioned above and the consequences of globalisation, which has favoured economic growth in cities while many rural areas have been left behind. This has fuelled resentment towards urban elites and reinforced the perception that rural interests are being ignored by traditional parties and public policies. In general, such attitudes have been clearly asymmetrical, being more prevalent among rural dwellers.

Álvaro Sánchez-García is PhD researcher at the University of Salamanca. He is also a member of the research project “Geography, Polarization and the Rural-Urban Divide in the XXI Century”. His research interests are political geography, populist radical parties, and rural-urban studies.

Twitter: @alsanchezgarcia

Bluesky: asanchezgarcia.bsky.social

Website: https://asanchezgarcia.github.io